|

The family of Chief Nas-wau-kee and Doga (also spelled Dogah or Togah) was the honored Potawatomi family at the Trail of Courage Living History Festival Sept. 17-18, 2011. Their history is recorded in the George Winter journals, published by the Indiana Historical Society in 1948 and 1993. Nas-wau-kee’s picture was sketched and then his portrait painted by Winter. A copy of the original painting is now at Culver Museum. George Winter met Nas-wau-kee in July 1837 at the council at Lake Kee-wau-nay (now Lake Bruce) in Fulton County. Winter rented a room in Mas-saw’s log cabin, paying $1 a day for meals which Doga (aka Togah) cooked. Winter slept on the floor on his own blanket. He made many sketches of the Potawatomi and wrote details of their clothing so he could paint portraits later. Winter mentioned that Doga could speak English with some fluency. Michale Edwards, Moore, OK, represented the Nas-wau-kee family. She is a retiree of the U.S Postal Service. She has been doing genealogy research and is writing a book to be published later this year. A key to the city of Rochester was presented to her at the Trail of Courage opening ceremony at 10 a.m. Sept. 17 by City Councilman Barry Hazel. A historical marker for Chief Nas-wau-kee was dedicated Sept. 16 at 5 p.m. at Culver. A crowd of about 50 attended. The marker is a big boulder with a metal plaque, the Eagle Scout project of Bryan McKinney, Winamac Troop 229, which has several members from Culver also. Bryan is a senior at Winamac High School. The historical marker is located in the Culver park just east of the beach, at the start of the “Indian Trails” that lead to Culver Military Academy. A carry-in supper was held immediately after the dedication at the home of Rick and Julia Baxter at 16787 - 18 B Road. This house is located on the former Nas-wau-kee reservation. Nancy Baxter, author of several books about Indiana history, provided drinks and tableware. About 20 people attended. The annual meeting of the Potawatomi Trail of Death Association was held after supper. Nas-wau-kee was a prominent chief and speaker in Marshall and Fulton counties. Six treaties have Nas-wau-kee’s name spelled several different ways, which he signed with an X. Winter spelled it several ways, mostly Nas-waw-kay but also Knas-waw-kay. The family prefers the spelling Nas-wau-kee. The spellings of American Indian names in historic documents usually have hyphens. This is because the scribe/ interpreter at the treaties wrote what he thought the Indian said his name was. Often the spelling is in French phonics, rather than English. He signed the treaty of 1826 with his name spelled Nasawauka. This treaty provided for a grist mill and blacksmith shop at Lake Manitou and payment for a strip of land a mile wide for the Michigan Road from the Ohio River to Lake Michigan. His name was spelled Nees-waugh-gee within the treaty of October 26, 1832, but as Nas-waw-kee in the signature line at the end of the treaty. The treaty ceded most of northern Indiana and reserved sections of land to various chiefs, including three sections of land for Nas-waw-kee and his brother Quash-qua. The next day, Oct. 27, 1832, he was given one section of land and his name was spelled Nas-wau-kee. This set aside one section for him alone, but he and his brother Quash-qua received three sections at Lake Maxinkuckee reserved for their families and their bands. He signed three treaties in 1836: his name was spelled Nas-waw-kee on April 22 and Nas-waw-kay on August 5. In these treaties he ceded his reservation land (2 sections at Lake Maxinkuckee) and agreed to go west of the Mississippi River. At the treaty of Sept. 23, 1836, the name Nas-waw-ray was spelled yet another way. At the council in July 1837 at Lake Kee-wau-nay (now Lake Bruce) he gave a heart- rending speech on why the Indians did not want to go west. The artist George Winter attended this council in 1837 and sketched him, spelling his name as Nas-waw-kay.  In August 1837 Nas-wau-kee called his white neighbors together near his village at Lake Maxinkuckee at present- day Culver and gave a tearful farewell speech, shaking everyone’s hand. (This farewell speech was published in “Removal of the Pottawattomie Indians from Northern Indiana,” by Daniel McDonald in 1899.) The next day he led his band to Chief Kee-wau-nay’s village and on to Logansport, joining Chief Kee-wau-nay’s band for the journey to Kansas. There were 47 Potawatomi; and no deaths occurred (unlike the 1838 Trail of Death in which 42 died of 859 Potawatomi on the trip). The removal was called an emigration by the U.S. government and began Aug. 23, 1837, led by George Proffit. On the trip Proffit recorded that Nas-waw-kay was sick with cholera for three days. The group of 47 Potawatomi arrived in Kansas Oct. 23. Nas-waw-gee called for a priest so Father Christian Hoecken came and established St. Mary’s Mission at Sugar Creek, where the Potawatomi lived until 1848-49. His name is carved on a historical marker at Sugar Creek as Nesfwawke. (The f was really an s as it was often written in that time period with the lower loop backwards from the cursive f and is mistaken for f today.) His name is not found in the Sugar Creek burial records 1838-1849 but three pages are missing. The following year Menominee’s large group of Potawatomi, called the Mission Band or Wabash Band, arrived from northern Indiana on Nov. 4, 1838, at the end of the Trail of Death. They had suffered greatly and lost 42 members to death along the trail. They lived at Sugar Creek for 10 years, and 639 were buried there. Chief Menominee died April 15, 1841, at Sugar Creek. Many of the Potawatomi today can find their ancestors’ names on the seven crosses at Sugar Creek. In 1848-49 the Potawatomi moved further west to a new mission at St Marys, Kansas, where they signed a new treaty creating the Citizen Band of Potawatomi in 1861. Nas-wau-kee’s name is not on the Treaty of 1861, so he probably died at Sugar Creek. It is noted that when they were baptized, they were given “Christian” names, usually retaining their Indian name as their surname. Thus Menominee became Alexis Menominee. The Sugar Creek mission is now the St. Philippine Duchesne Memorial Park about 20 miles south of Osawatomie, Kansas. Mother Duchesne was an elderly nun who served as a missionary to the Potawatomi at Sugar Creek 1841-42. The Potawatomi named her “She Who Prays Always.” She was canonized in 1988, the first female saint west of the Mississippi River. The Catholic diocese bought 450 acres and set up the memorial park. See section on St Philippine Duchesne for pictures and history of her and the park. There is a picture of the wooden plaque that names Nesswawke. Nas-wau-kee had at least two daughters. One was married to Joseph Barron in 1837, as mentioned by George Winter at the Lake Kee-wau-nay council. His other daughter was married in January 1838 at Sugar Creek by Father Hoecken, the missionary who ministered to and worked with the Potawatomi from Indiana. He came to Sugar Creek at the request of Nas-wau-kee and married Nas-wau-kee’s daughters. Nas-wau-kee had a maternal niece named Togah or Dogah (spelled Doga by George Winter), who received rights to a reservation in the October 27, 1832, treaty. (The treaty was held at the Tippecanoe River north of Rochester, Indiana.) Article III of the 1832 treaty says “To To-gah, a Potawatomi woman, one quarter section.” It is reported that Togah was cheated out of her reserve, and the government sold her land to white people when the land patent was pending. Her maternal nephew was Michale’s great- great- grandfather, Thomas Wezoo aka Wesaw. He sought to right this grievous wrong but was never able to do so in his lifetime. Nas-wau-kee also had two nephews. M’joquis and Iowa (also spelled I-o-wah). You can read more about Doga, M’joquis and Iowa in the George Winter journals. Winter painted portraits of Iowa and Nas-wau-kee as they were considered headmen and chiefs of the Wabash Potawatomi. Nas-wau-kee had a brother, Quash-qua, who also received a reservation in the October 26, 1832, treaty negotiations and was located at Lake Maxinkuckee beside Nas-wau-kee’s reservation. Nas-wau-kee’s sister was married to Chief Aubbeenaubbee who negotiated the October 26 and 27, 1832, treaties. He was awarded 36 sections of land at this treaty on October 26 and 10 sections October 27, equaling 46 square miles, making him the biggest landowner in several counties. The Mackety family descends from Nas-wau-kee and Dogah through Thomas Wezoo (Wesaw). His Civil War record states he was born Thomas Wesaw. His name likely migrated to “Wezoo” from his association with Wezo Motay Wesaw, an ancestor. Thomas Wezoo is the father of Elizabeth Wezoo, who married Albert Mackety. Albert Mackety was the early 1900s leader of the Nottawaseppi Huron Potawatomi band located at Athens, Michigan. Albert and Elizabeth Mackety had six children: five boys and one girl: Delbert, Herbert, David, Thomas, Sam and Alberta Mackety. Michale’s generation of Macketys are the grandchildren of Albert and Elizabeth. Michale was placed for adoption as a newborn baby. She is 9/16 Potawatomi blood quantum by her biological mother and father. Michale found her biological family in 1992 and met them at an Oklahoma pow wow in 1998. Michale is currently studying Native American History at Oklahoma University. Since 2004 she has been extensively involved in Potawatomi genealogy, specializing in Indiana and Michigan Potawatomi families. Her lineal descent is Nottawaseppi Huron, Pokagon and Canadian Potawatomi. The village of Notta-wa-si-pa is mentioned in the Oct. 27, 1832, treaty. Michale has three daughters: Erin, age 22; Taylor and Trae Edwards -identical twins, age 20. Taylor accompanied Michale to the Trail of Courage. They gave a program at Culver Elementary School on Sept. 16 at 12:45 p.m. They were introduced at the Trail of Courage opening ceremony at10 a.m. Sept. 17 and 18. They told about their family history 10:30-11:00 both days. They were also honored at the Indian dances at 2 p.m. We are happy that this family is sharing their history with the people of Indiana, a land where their ancestors lived over 170 years ago. Potawatomi Chief Nas-wau-kee Prominent chief and speaker Nas-wau-kee (or Nees-waugh-gee) signed several treaties with the U.S. government. In 1836, he ceded his two sections of land just east of Lake Maxinkuckee and regretfully agreed to go west within two years. Spelling the chief’s name as Nas-waw-kay, the artist George Winter sketched him at the Lake Kee-wau-nay (now Lake Bruce) treaty council of July 1837, where he gave a heart-rending speech on why the Indians did not want to leave. In August, Nas-wau-kee called his white neighbors together at his village and gave a tearful farewell address, shaking everyone’s hand. His band joined Chief Kee-wau-nay’s band to be conducted by George Proffit to Kansas. The 47 Potawatomi journeyed from August 23 to October 23, 1837, without loss of life (unlike the 1838 Trail of Death, on which 42 died of 859 Potawatomi on the trip). At Nas-wau-kee’s urging, Father Christian Hoecken established St. Mary’s Mission at Sugar Creek, Kansas, where the Potawatomi lived 1838-1849. A historical marker there records the chief as Nesfwawke. The Mackety family, from the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, are Nas-wau-kee’s known descendants. Eagle Scout project of Bryan McKinney. Erected 2011. Historical groups and a local Eagle Scout candidate are hoping the community will step up to honor a local Potawatomi Indian chief who left his mark not only on the Culver-Lake Maxinkuckee area, but in the state of Kansas as well. Descendents of Chief Nas-waw-kee, whose village occupied land on the east shore of the lake, will be honored at the annual Trail of Courage festival Sept. 17-18. During correspondence with Michale Edwards of the Nas-waw-kee family, the idea of a historical marker for Chief Nas-waw-kee was conceived. Shirley Willard of the Potawatomi Trail of Death Association, a branch of the Fulton County Historical Society, began an effort to place a monument in the chief’s honor in the Culver area. The town park was chosen as a location of public visibility, and a boulder placed at the start of the “Indian trails” between the park and Culver Academies’ campus. Willard has assisted with erecting historical markers on the Trail of Death for many years. Over 80 historical markers have been erected with donations at no expense to taxpayers. Bryan McKinney, a senior at Winamac Community High School and member of Boy Scout Troop 229 there (several Culver families are also members of the Troop) took an interest in obtaining permission to place the monument in the park, located and had placed the stone in an approved spot, landscaped around it, and helped arrange for and will assist with the mounting of the plaque honoring the chief. “I didn’t want an easy project to earn the rank of Eagle,” says McKinney. “I was also excited about it because it was a historical monument that could be there for the next 100 years. When I had just bridged over from Cub Scouts and joined the Boy Scout troop six years ago, I remembered another Eagle project where the Scout placed a Civil War monument at the Courthouse Square in Winamac, and I was always impressed with that project. So a historical monument honoring the Native Americans that lived in this area over 170 years ago seemed a very worthwhile project.” With the support of the Antiquarian and Historical Society of Culver, donations are being sought to offset the $750 cost of the plaque itself, the last step in the monument process. Because the plaque needs to be ordered by Sept. 3 in order to be done in time, donations need to be sent as soon as possible. Donations can be sent to the Potawatomi Trail of Death Assn., Fulton Co. Hist. Soc., 37 E 375 N, Rochester IN 46975. The FCHS is a 501-C3, non-profit organization.  Maxinkuckee Chief, descendants honored

Maxinkuckee Chief, descendants honored

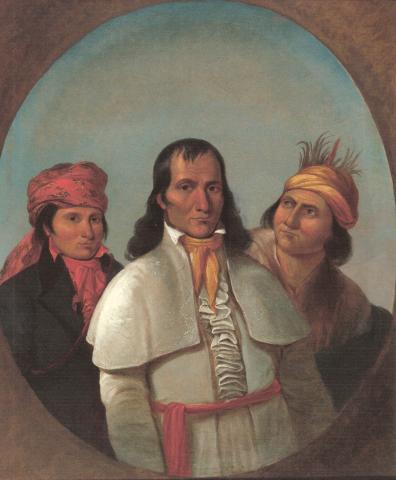

Photo from The Pilot News, Plymouth Indiana, by Jeff Kenney, Culver Descendants and organizers gathered Friday Sept. 16, 2011, to dedicate a historical marker to Chief Nas-wau-kee, a Potawatomi chief who lived on the east shore of Lake Maxinkuckee until 1837. On hand was the chief’s great- great- great- grand- niece Michale Edwards, who traveled from Oklahoma for the event and who discussed with the audience her discovery of her relation to the chief, who she described as “gentle, mild- mannered and trusting.” The monument is located in Culver’s town park just east of the beach. Back row, from left: Scouts Damien Stout, Brian McKinney - who did the marker for his Eagle Scout project, Shawn DePoy, Jacob Connor, Jack Campbell, Dawson Ploss, Alan Dilts, Austin Felty, Jeremy Penrod, and Jim Sawhook of Culver Antiquarian and Historical Society. Front row: Taylor Edwards and mother Michale Edwards, Delores Grizzell - secretary of Potawatomi Trail of Death Assn., Shirley Willard - PTDA treasurer, Bill Willard, and Dr. George Godfrey, president of Potawatomi Trail of Death Assn. At left: an 1800s painting of Chief Nas-wau-kee by George Winter, courtesy of The Wisconsin Historical Society. Thanks to the following: Culver Park Department, Culver Antiquarian & Historical Society, Marshall County Tourism, Leonard Bennett, Culver, for attaching the plaque to the boulder; Marcia Adams, Culver; Dan & Dana (Richards) Skulan, Kewanna; Steve & Sherry McKinney, Winamac; Melissa Christiansen, Plymouth; Tippecanoe River Wythougan Daughters of American Revolution; Carol Layman, North Vernon; Jeannie Wamego Van Veen, Tahlequah, OK; Carmelita Wamego Skeeter, Tulsa, OK; Dolores Grizzell, Winamac, Nancy & Arthur Baxter, Indianapolis; Potawatomi Trail of Death Association - branch of Fulton County Historical Society, Rochester. And in memory of Marjorie Terpstra by Rae Ann Carswell, Danville, IN. Thanks for the four flags from Potawatomi nations: Citizen Band in Oklahoma, Prairie Band in Kansas, Forest Band in Wisconsin, and Pokagon Band in Michigan and northern Indiana. These flags were donated to the Potawatomi Trail of Death Association. Taking part in the dedication were Boy Scout troops 229 and 209/Cub pack 290 of Winamac and Culver - presenting the colors, Steve McKinney - Scoutmaster Troop 229; Jim Sawhook, Culver Antiquarian & Historical Society, Shirley Willard, Fulton County Historical Society, also treasurer of Potawatomi Trail of Death Assn.; Michale Edwards, Moore, OK, - descendant of Nas-wau-kee; Dr. George Godfrey, president of Potawatomi Trail of Death Assn - blessing to the four directions; Bryan McKinney - thanks to all who helped. When George Winter heard about the Indian Council to be held at Lake Kee-wau-nay (now Lake Bruce) in July 1837, he decided to go. He wanted to draw sketches of the Potawatomi so he packed his pencils and pads in his saddle bags for the trip from Logansport. He described this in an article for the Logansport newspaper and the articles were published in “The Journals and Indian Paintings of George Winter 1837-1839” by the Indiana Historical Society in 1948. He wrote, “The 21st of July, 1837, is one that memory will ever bring before me, with all its associate pleasure.” He remained in the Indian camp for several days. He wrote of the wild flowers, the bright unclouded weather, the forest trees, and the Indian activities. He witnessed not only the council, led by Col. Abel C. Pepper, in which he urged the Potawatomi to go west. He also witnessed a burial, a dance in the evening, and card games in Mas-saw’s log house, where he stayed. He paid $1 a day to sleep there on the floor on his own blanket, with 20 other white men. He put a board across an empty flour barrel to make a table for his art work. He wrote that Doga assisted with the cooking and that she was a good cook. In the cool shade of the forest, the council was held. Pepper and his agents sat at a table while the Indians sat or stood in various groups. Winter sketched the scene, hoping to sell a painting of it later but Pepper did not have funds to buy it so Winter never made an oil painting of it. The Potawatomi were not eager to gather, for in the past the treaties had not held any bargains for them. At last a tall and dignified figure approached the council place. It was the “speaker,” followed by the chiefs, head men and warriors. They took seats up on a fallen tree and were painfully silent. Pepper told the gathered Indians about the friendship of their Great Father, the President - that he had their interests at heart and had prepared a home for them in the Far West, where as a nation they would grow in vigor and strength. The country even exceeded the fertility of Indiana, the climate milder, and they would find game in abundance. He mentioned their present miseries and reminded them that they had sold their land and agreed to go West. The speaker was Nas-wau-kay (aka Nas-wau-kee, Nees-waugh-kee, and other spellings), with long and flowing hair, wearing a white counterpane coat. He was educated and spoke of all the treaties from the time of General Wayne down to the last made in 1836. “Now Father, everything I say comes from the heart. We wish our money to be paid here not west of the Mississippi. You have been speaking of our miseries and wretchedness. Your counsels have brought these miseries on us. By your advice the very lands on which we expected to terminate our existence have been sold from us. “Father, we do not see why it is that we should be requested to go west and live long. Man’s life is uncertain, and ere we reach that country, death may overtake us. I see not how our natural existence should be prolonged by going west. ..” Thus did Nas-wau-kee try to buy time and stay in Indiana. He had probably heard that Kansas was not better than Indiana. A delegation of Potawatomi had gone to Kansas a few years earlier and reported that it was not a paradise of tall trees, many streams filled with fish, etc. They liked Indiana better. That night the Potawatomi danced. Two poles were planted in the ground and a fire built between them. Winter described the people who danced, both white men and Indians, the movements, how the women seemed to shuffle while the men were energetic. Chief Wee-saw was called upon to open the dance. M-jo-quiss and Wee-wiss-sa, two chiefs who were brothers, danced with admirable grace. “Yelling, whooping and laughing were the constant accompaniments of the festivity,” Winter wrote. The next day, Sunday, the council resumed. Pepper was called elsewhere by duties, so Col. Sands and George Profit took his place at the table. Nas-wau-kay apologized for his harsh words of the previous day and said they would go west. “We know you are wise. We know you are strong. You say you love your red children, and when we meet you again, we will be ready to do what you say.” He shook hands with Col. Sands. “Father! For myself, I know my situation. You have told it truly, Since you have been a Nation, you have been fortunate and unfortunate. I have had no reverses. I have always been unhappy.” Nas-wau-kay and his brother, Quash-qua, had reservations at Lake Maxinkuckee, Culver, Indiana. The following month, Nas-wau-kay called his white neighbors together and bid them farewell, shaking everyone’s hands. His band and Chief Kee-wau-nay’s band went to Logansport and then on to Kansas, conducted by George Profit. The 47 Potawatomi journeyed from August 23 to October 23, 1837, without loss of life (unlike the 1838 Trail of Death, on which 42 died of 859 Potawatomi on the trip). Nas-wau-kay was sick with cholera for three days but he recovered. (The journal for Chief Kee-wau-nay and Nas-wau-kay’s Emigration was published in the Fulton County Historical Society Quarterly no. 68 in 1988. It is still for sale at the museum.) When they arrived in Kansas, Nas-wau-kee asked Father Christian Hoecken to come. Hoecken established St. Mary’s Mission at Sugar Creek, Kansas, where the Potawatomi lived 1838-1849. A historical marker there records the chief as Nesfwawke. It is not known when Nas-wau-kee died. |

| < Previous | Home | Next > |